“I think where I am not, therefore I am where I do not think. I am not whenever I am the plaything of my thought; I think of what I am where I do not think to think.”- Jacques Lacan

In 1929, a man named Edward Bernays was tasked by Lucky Strike executives to make cigarettes more appealing to women. Smoking had long been considered a corrupt and filthy habit for women, and the cigarette often found itself parroted as a symbol of feminine vice or ill moral health.[1]

To overcome this resistance to the idea of women being seen smoking Bernays conducted an elaborate public relations campaign, known colloquially as ‘Torches of Freedom’. The intention was to reposition the cigarette as a symbol of female emancipation. To create the idea that the act of smoking was in and of itself revolutionary for women. At the 1929 Easter Day Parade in New York City, Bernays hired a group of actors to appear in the parade, smoking cigarettes and proclaiming them as a symbol of freedom.

Bernays’ plan worked. In 1923, women only purchased 5% of cigarettes sold; in 1929 that percentage increased to 12% and throughout the early 1930s, grew exponentially to 33.3%, where it remained until 1977. In a commercial sense, the campaign had effectively neutralised this widespread opposition to women smoking cigarettes. Although the attitude naturally continued, the unseen forces operating inside our unconscious had found themselves changed unutterably.

A relative of Sigmund Freud, and a keen expositor of his ideas, Bernays also believed that the human mind is subject to unknowable drives and desires. That the active ‘self’ where we think and formulate our mind is subject to forces and patterns of influence that dictate our every waking moment and desire.

Bernays used the work of his Uncle Sigmund to develop strategies around how information should be disseminated and controlled, creating the field of public relations as we know it today. He believed that industries and governments are better able to control the thinking of the public than we could ever know, and that large-scale campaigns and messaging have an unconscious effect on the populace in ways that have had huge repercussions for consumers. In a short few years, Bernays was able to change the public’s perception of female smokers from women with perishing moral fibre to champions of a new future. Brands soon began to market exclusively to women, particularly with the advent of the cigarette filter in the 1950s. Marlboro originally marketed their cigarettes as ‘mild as May’ to promote the product to women and further spread the misconception that filtered cigarettes are safer and milder than the alternative.

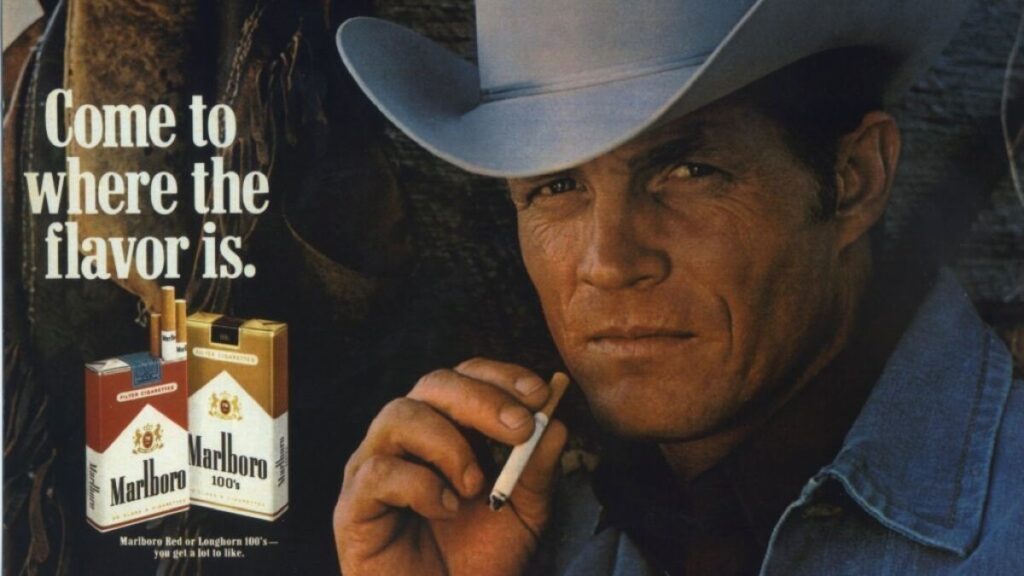

In the late 1950s however, Marlboro found itself at another impasse. Their cigarettes had been marketed towards women, at a time when reports about the dangers of smoking began to make their way into the headlines. Many men were apprehensive to smoke a filtered product, as they had for so long been targeted exclusively at women. Marlboro needed to find a way to reinvent its brand and reintroduce itself to the male-dominated market.

That reinvention was the ‘Marlboro Man’. Leo Burnett, the Chicago ad man in charge of the rebrand, was struck by how much of the advertising about cigarette filters was concerned with scientific jargon and technical detail about how well cigarette smoke was filtered. Burnett thought dwelling on the effectiveness of filters still forced consumers to consider the long-term effects of smoking, which is something he was keen to remedy.

Burnett proposed to use classic portraits of American masculinity: cowboys, construction workers, sea captains, or even weightlifters to help sell cigarettes. Burnett caught an image of a cowboy in Life Magazine and decided that was the best fit for the campaign. Much like Bernays all those years before him, it worked. Within a year, Marlboro’s market share had grown from less than 1% to the fourth biggest brand in the American domestic cigarette market, with net profits of $20 billion.

But what can these campaigns teach us about the importance of image and messaging? Both campaigns relied on an ability to actively change consumers’ minds, by using their own ideology and worldview to affirm or dissuade their attitudes toward smoking. This approach was remarkably effective, particularly so with Marlboro as they were able to deflect from increasingly prevalent reports of the dangers of smoking with the sheer power of their brand.

We still see shades of this approach to marketing every day. In the 20th century, brands used consumers’ insecurities and shifting cultural attitudes to project images of masculinity and femininity onto products. Owning that product qualified the consumer to live up to that very image. Nowadays, consumers’ attitudes to the world around them are reflected in the products themselves.

The visual language of marketing has changed, but its messaging and intentions have been consistent: to change the minds of consumers. The most effective way to do that is to have your brand project an image of what consumers want, and whom they want to be. The players may have changed, but the game remains the same.